Describe different creative thinking techniques and how they work

The text below introduces the four types of creative thinking.

1. Reframing

Reframing opens up creative possibilities by changing our interpretation of an event, situation, behaviour, person or object.

Creative frames of reference

Here are some frames to help you generate creative solutions. Next time you’re facing a creative challenge or are stuck on a problem, run through this list and ask yourself the questions. Once you’ve done this a few times, you should get into the habit of asking yourself these questions, and making creative use of reframing.

- Meaning — what else could this mean?

- Context — where else could this be useful?

- Learning — what can I learn from this?

- Humour — what’s the funny side of this?

- Solution — what would I be doing if I’d solved the problem? Can I start doing any of that right now?

- Silver lining — what opportunities are lurking inside this problem?

- Points of view — how does this look to the other people involved?

- Creative heroes — how would one of my creative heroes approach this problem?

2. Mind Mapping

When you make notes or draft ideas in conventional linear form, using sentences or bullet points that follow on from each other in a sequence, it’s easy to get stuck because you are trying to do two things at once: (1) get the ideas down on paper and (2) arrange them into a logical sequence.

Mind mapping sidesteps this problem by allowing you to write ideas down in an associative, organic pattern, starting with a key concept in the centre of the page, and radiating out in all directions, using lines to connect related ideas. It’s easier to ‘splurge’ ideas onto the page without having to arrange them all neatly in sequence. And yet an order or pattern does emerge, in the lines connecting related ideas together in clusters.

Because it involves both words and a visual layout, it has been claimed that mind mapping engages both the left and right hemispheres of the brain, leading to a more holistic and imaginative style of thinking. A mind map can also aid learning by showing the relationships between different concepts and making them easier to memorize.

Visual approaches to generating and organising ideas have been used for centuries, and some pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks are often cited as the inspiration for modern mind maps. Tony Buzan is the leading authority on mind mapping. Among his tips for getting the most out of the technique are:

- Start in the centre of the page

- The lines should be connected and radiate out from the central concept

- Use different colours for different branches of the mind map

- Use images and symbols to bring the concepts to life and make them easier to remember

3. Insight

The word insight has several different meanings, but in the context of creative thinking it means an idea that appears in the mind as if from nowhere, with no immediately preceding conscious thought or effort. It’s the proverbial ‘Aha!’ or ‘Eureka!’ moment, when an idea pops into your mind out of the blue.

There are many accounts of creative breakthroughs made through insight, from Archimedes in the bath tub onwards. All of them follow the same basic pattern:

- Working hard to solve a problem.

- Getting stuck and/or taking a break.

- A flash of insight bringing the solution to the problem.

- Gathering knowledge — through both constant effort to expand your general knowledge and also specific research for each project.

- Hard thinking about the problem — doing your best to combine the different elements into a workable solution. Young emphasises the importance of working yourself to a standstill, when you are ready to give up out of sheer exhaustion.

- Incubation — taking a break and allowing the unconscious mind to work its magic. Rather than simply doing nothing, Young suggests turning your attention “do whatever stimulate your imagination and emotions” such as a trip to the movies or reading fiction. (Remember what the neuroscientists say about being happy rather than anxious.)

- The Eureka moment — when the idea appears as if from nowhere.

- Developing the idea — expanding its possibilities, critiquing it for weaknesses and translating into action.

4. Creative Flow

You know that feeling you get when you’re completely absorbed in your work and the outside world seems to melt away? When everything seems to fall into place, and whatever you’re working with — ideas, words, notes, colours or whatever — start to flow easily and naturally? When you feel both excited and calm, caught up in the sheer pleasure of creation?

I have some good news for you. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmahalyi has studied this state — which he calls creative flow — and concluded that it is very highly correlated with outstanding creative performance. In other words, it doesn’t just feel good — it’s a sign that you’re working at your best, producing high-quality work.

Csikszentmahalyi has described nine essential characteristics of flow:

- There are clear goals every step of the way. Knowing what you are trying to achieve gives your actions a sense of purpose and meaning.

- There is immediate feedback to your actions. Not only do you know what you are trying to achieve, you are also clear about how well you are doing it. This makes it easier to adjust for optimum performance. It also means that by definition flow only occurs when you are performing well.

- There is a balance between challenges and skills. If the challenge is too difficult we get frustrated; if it is too easy, we get bored. Flow occurs when we reach an optimum balance between our abilities and the task in hand, keeping us alert, focused and effective.

- Action and awareness are merged. We have all had experiences of being in one place physically, but with our minds elsewhere — often out of boredom or frustration. In flow, we are completely focused on what we are doing in the moment. Our thoughts and actions become automatic and merged together — creative thinking and creative doing are one and the same.

- Distractions are excluded from consciousness. When we are not distracted by worries or conflicting priorities, we are free to become fully absorbed in the task.

- There is no worry of failure. A single-minded focus of attention means that we are not simultaneously judging our performance or worrying about things going wrong.

- Self-consciousness disappears. When we are fully absorbed in the activity itself, we are not concerned with our self-image, or how we look to others. While flow lasts, we can even identify with something outside or larger than our sense of self — such as the painting or writing we are engaged in, or the team we are playing in.

- The sense of time becomes distorted. Several hours can fly by in what feels like a few minutes, or a few moments can seem to last for ages.

- The activity becomes ‘autotelic’ – meaning it is an end in itself. Whenever most of the elements of flow are occurring, the activity becomes enjoyable and rewarding for its own sake. This is why so many artists and creators report that their greatest satisfaction comes through their work. As Noel Coward put it, “Work is more fun than fun”.

Below are eight of my favourite creative problem solving techniques. These don’t just apply to content creation either, they can be used in all aspects of life.

1. Mind Mapping

Let’s begin with a timeless classic. Mind mapping (aka brainstorming or spider diagrams) is the little black dress of idea generation; it never goes out of fashion. It almost feels wrong to walk into an agency and not see some form of mind map on a whiteboard somewhere.

The key to mind mapping is to take note of every idea that comes up. Don’t neglect anything, no matter how far-fetched it may seem. Save the critical selection process for later. Generate as many ideas as possible; the more you jot down, the bigger chance of finding that golden ticket idea.

2. The Checklist

Young children are amazingly creative. Their curiosity, imagination and thirst for knowledge seem boundless. They ask questions about everything, because practically everything is new to them. If you’ve ever played the ‘Why?’ game with a kid, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about*. It’s infuriating, yet surprisingly enlightening.

As we get older, we tend to stop asking so many questions. We accept a lot more, because it’s all been explained to us before. Perhaps it’s because of this, that adults are stereotypically perceived as having very little imagination.

Maybe if we asked more questions, our content might be a little bit more imaginative. This is where the checklist technique can help. This is essentially a list of questions which you should ask yourself before beginning your work.

Alex Osborn, who is often coined as the father of brainstorming, established around 75 creative questions to help encourage ideas in his fantastic book, Applied Imagination. It’s well worth a read if you can get hold of it, but to give you a head start, there are six universal questions that can be asked:

- Why?

- Where?

- When?

- Who?

- What?

- How?

Ask yourself these question (in some form) every time you create content, and chances are you’ll come up with some pretty interesting answers.

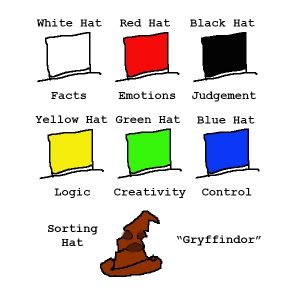

3. Six Thinking Hats

(Disclaimer: This is a technique that could prove potentially confusing to all the SEOs out there, as a few may be a bit weary at the prospect of wearing a black hat)

Developed by Edward de Bono in the early 80s, this popular technique is now used by businesses all over the world. They involve putting on a selection of metaphorical hats when it comes to making a decision. Each hat represents a different direction of thinking.

- White Hat – Facts

- Red Hat – Emotions

- Black Hat – Judgement, Caution

- Yellow Hat – Logic

- Green Hat – Creativity

- Blue Hat – Control

This method can be used in a group or on your own, and you may find yourself ‘wearing’ more than one hat at once (Of course if you’re really bored you could always physically make the hats for instant entertainment!). You can use the hats to take the ego out of the equation. They let you think and decide on topics in a rational yet creative style.

4. Lateral Thinking

Another term coined by Dr. de Bono, this involves looking at your situation in a different way. The simplest answer is not always right. We solve most problems in a linear fashion, i.e. if something happens it must have been… because of….

We take a step by step approach to finding our answers. De Bono encouraged others to look at their situation differently, to step sideways for a second if you will. This allows people to re-examine their predicament from a much more creative point of view.

Say for example you have a client who sells tractors. If you were thinking in a linear fashion, you may feel the need to create content about how great tractors are because you need to sell tractors. Thinking about things laterally though opens up a world of possibilities. Try looking at the bigger picture.

Tractors are a key component to farming, farming produces food and resources. Farms also house animals. A popular children’s rhyme about farm animals is Old McDonald, you may wonder how that rhyme came to be. Why not create content around the origin of that rhyme?

That’s just a (very) basic example, but you can clearly see how lateral thinking can be used to help inspire you.

5. Random Word Generation

I love this technique. Simply pick two random words and try and tie your content to it in the most imaginative way possible. Simple as that.

The real fun part is how you choose to come up with the words. You could use an online generator; you could flick through a dictionary; or you could write words on a bunch of plastic balls, throw them into the air, and then choose the words on the first two balls you catch. Have fun.

6. Picture Association

If you’re truly stuck for ideas, perform an image search on your topic of choice, pick a random photo. Work backwards from the picture, developing a story around how the photo was taken.

For example, if you see a picture of a dog looking up at the night sky, ask yourself what it could be thinking. Is it a stargazing dog? Does that dog secretly long to be an astronaut? Perhaps a story about a space dog would be awesome! In fact a space dog would make a great mascot for any business so we could look at the best business mascots. So on so forth.

This may be considerably harder with stock photos, but characterise the people within the image and the more imaginative of you out there will prevail to develop some fantastic ideasthrough this technique.

7. Change Perspective

This can often be hard to do, but try putting yourself in other people’s shoes. Sometimes you can get too attached to your own work, I know I always do it. You may be too close to notice that there are faults visible from afar.

Share your ideas with others, and get a fresh pair of eyes to look at your work. Encourage constructive criticism, you don’t have to take it all on board, but it may offer up some seriously beneficial observations.

8. Get Up and Go Out

People underestimate the value of being bored. If you work around screens all day, if can often prove both relaxing and rewarding to just get up and walk about for a bit. Let your mind wander instead of focussing on a task so hard it hurts.

Take a walk around your local woods, indulge yourself in your own personal contemplation montage as you skim rocks across a pond. Let the miracle of nature, and that brief moment of what is hopefully peace and quiet, inspire and energise you.

Similarly, many believe that the practice of meditation, clearing their mind of all thoughts and allowing themselves to be at peace, is a fantastic method to help spur creativity. Although I’ve never personally tried it, I can see how people might find it rewarding.

Our very own Mike Essex has already recorded a Koozai TV video covering some really resourceful tips on how to be more creative with your work, including time management exercises such as Blocking and the Pomodoro technique. Check out the video below for more information:

1.2 Describe how creative thinking has developed over time and its impact on society

History of the concept of creativity

Ancient views

Most ancient cultures, including thinkers of Ancient Greece, Ancient China, and Ancient India, lacked the concept of creativity, seeing art as a form of discovery and not creation. The ancient Greeks had no terms corresponding to "to create" or "creator" except for the expression "poiein" ("to make"), which only applied to poiesis (poetry) and to the poietes (poet, or "maker") who made it. Plato did not believe in art as a form of creation. Asked in The Republic, "Will we say, of a painter, that he makes something?", he answers, "Certainly not, he merely imitates."

It is commonly argued that the notion of "creativity" originated in Western culture through Christianity, as a matter of divine inspiration. According to the historian Daniel J. Boorstin, "the early Western conception of creativity was the Biblical story of creation given in the Genesis." However, this is not creativity in the modern sense, which did not arise until the Renaissance. In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, creativity was the sole province of God; humans were not considered to have the ability to create something new except as an expression of God's work. A concept similar to that of Christianity existed in Greek culture, for instance, Muses were seen as mediating inspiration from the Gods. Romans and Greeks invoked the concept of an external creative "daemon" (Greek) or "genius" (Latin), linked to the sacred or the divine. However, none of these views are similar to the modern concept of creativity, and the individual was not seen as the cause of creation until the Renaissance. It was during the Renaissance that creativity was first seen, not as a conduit for the divine, but from the abilities of "great men".

The Enlightenment and after

The rejection of creativity in favor of discovery and the belief that individual creation was a conduit of the divine would dominate the West probably until the Renaissance and even later.

The development of the modern concept of creativity begins in the Renaissance, when creation began to be perceived as having originated from the abilities of the individual, and not God. This could be attributed to the leading intellectual movement of the time, aptly named humanism, which developed an intensely human-centric outlook on the world, valuing the intellect and achievement of the individual.

From this philosophy arose the Renaissance man (or polymath), an individual who embodies the principals of humanism in their ceaseless courtship with knowledge and creation. One of the most well-known and immensely accomplished examples is Leonardo da Vinci.

However, this shift was gradual and would not become immediately apparent until the Enlightenment. By the 18th century and the Age of Enlightenment, mention of creativity (notably in aesthetics), linked with the concept of imagination, became more frequent.

In the writing of Thomas Hobbes, imagination became a key element of human cognition; William Duff was one of the first to identify imagination as a quality of genius, typifying the separation being made between talent (productive, but breaking no new ground) and genius.

As a direct and independent topic of study, creativity effectively received no attention until the 19th century. Runco and Albert argue that creativity as the subject of proper study began seriously to emerge in the late 19th century with the increased interest in individual differences inspired by the arrival of Darwinism. In particular they refer to the work of Francis Galton, who through his eugenicist outlook took a keen interest in the heritability of intelligence, with creativity taken as an aspect of genius.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading mathematicians and scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz (1896) and Henri Poincaré (1908) began to reflect on and publicly discuss their creative processes.

Twentieth century to the present day

The insights of Poincaré and von Helmholtz were built on in early accounts of the creative process by pioneering theorists such as Graham Wallas and Max Wertheimer. In his work Art of Thought, published in 1926, Wallas presented one of the first models of the creative process. In the Wallas stage model, creative insights and illuminations may be explained by a process consisting of 5 stages:

- (i) preparation (preparatory work on a problem that focuses the individual's mind on the problem and explores the problem's dimensions),

- (ii) incubation (where the problem is internalized into the unconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening),

- (iii) intimation (the creative person gets a "feeling" that a solution is on its way),

- (iv) illumination or insight (where the creative idea bursts forth from its preconscious processing into conscious awareness);

- (v) verification (where the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied).

Wallas' model is often treated as four stages, with "intimation" seen as a sub-stage.

Wallas considered creativity to be a legacy of the evolutionary process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments. Simonton provides an updated perspective on this view in his book, Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity.

In 1927, Alfred North Whitehead gave the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh, later published as Process and Reality. He is credited with having coined the term "creativity" to serve as the ultimate category of his metaphysical scheme: "Whitehead actually coined the term – our term, still the preferred currency of exchange among literature, science, and the arts. . . a term that quickly became so popular, so omnipresent, that its invention within living memory, and by Alfred North Whitehead of all people, quickly became occluded".

The formal psychometric measurement of creativity, from the standpoint of orthodox psychological literature, is usually considered to have begun with J. P. Guilford's 1950 address to the American Psychological Association, which helped popularize the topic and focus attention on a scientific approach to conceptualizing creativity. (It should be noted that the London School of Psychology had instigated psychometric studies of creativity as early as 1927 with the work of H. L. Hargreaves into the Faculty of Imagination, but it did not have the same impact.) Statistical analysis led to the recognition of creativity (as measured) as a separate aspect of human cognition to IQ-type intelligence, into which it had previously been subsumed. Guilford's work suggested that above a threshold level of IQ, the relationship between creativity and classically measured intelligence broke down.

1.3 Explain how creativity can apply in both creative and non-creative contexts

- Creativity is about generating ideas or producing things and transforming them into something of value. It often involves being inventive, ingenious, innovative and entrepreneurial.

- Creativity is not just about special people doing special things. We all have the potential to be creative and creativity is a skill that needs to be developed.

- Most individuals believe they are not very creative. Creativity, however, is an increasingly valuable commodity in the modern world.

- Creativity embraces both hard and soft thinking. The most powerful creative thinking occurs when the left and right hemispheres of the brain combine to apply both generative and evaluative processes.

- The forming of collaborative, creative groups and partnerships helps to foster creativity.

'Imagination is more important than knowledge.' Albert Einstein

Innovation and creativity is in all industries

All industries will be using creative thinking in one form or another

Modern life and living you will have to use creative thinking, creativity and problem solving problems.

Explain the potential impact of creative thinking on individuals and businesses

Innovation, inventions and evolution of modern man

1.5 Identify the techniques that can be used for filtering diverse information